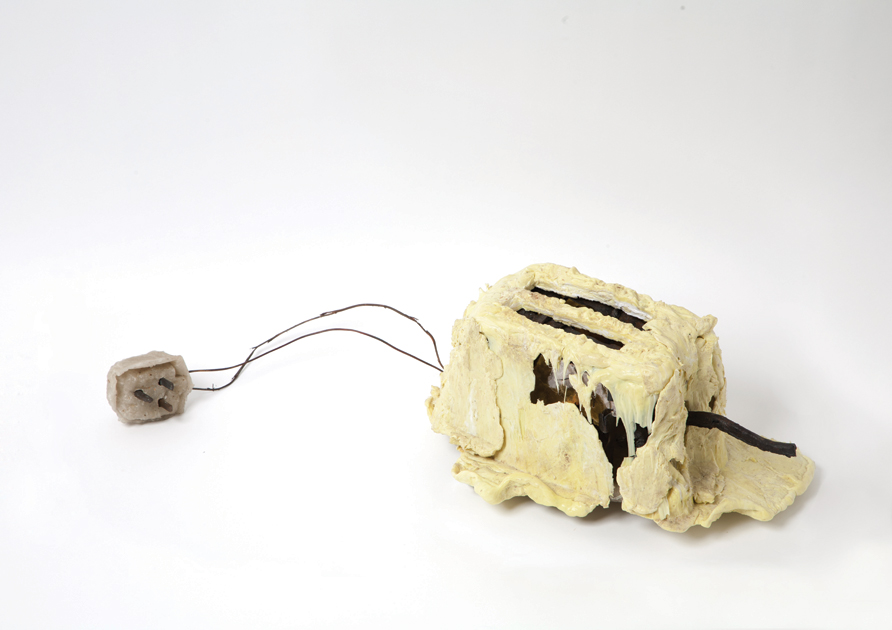

Conceptual Tool #9: A Toaster

(You should probably visit at least one of these links for this post to make sense.)

This toaster, something of an absurdist take on the modern economy, is a striking example of the interdependent nature of production. Econ professors particularly enamored with capitalism enjoy pointing to such examples (a simple pencil, designed in the Germany, assembled in Vietnam, made with South American graphite and African cedar--miraculous!) as proof of the amazing organizing power of trade and free markets. That power is pretty cool, but there is another lesson to be learned from this complexity.

The flip side of these miracles is that, on our own, we are incredibly inefficient. This was the lesson of Adam Smith's Pin Factory, where workers can produce far more pins if they work within a coordinated division of labor and each concentrate on a single task.

But where does a pin factory come from? Or more generally, how do we achieve the organizational sophistication and capital concentration required to make pin factories work? Factories do not simply spring up spontaneously--they must be planned and built, workers must be hired and managed, and capital must be purchased. In order to create these efficiencies due to specialization we have to organize ourselves, work with others, and pool risks and resources. Our ability to do these things does not derive wholly from ourselves or from some anarchic state of nature--instead we rely on an institutional framework that renders our economic actions coherent.

The case of the toaster is illustrative. To create a modern, efficient toaster--and to create the market networks that have facilitated its creation--we have built an almost incomprehensibly complex web of national and international laws enforced by armies and set by political processes. These laws enable specialization and help minimize the cost of resources, including labor.

To be sure, there has been trade around the world for centuries and even millennia. But it was not hunter-gatherers or subsistence farmers producing or distributing these goods--it was complex systems of city-states, empires, and other hierarchies of power. Today, where laws do not bound and regulate markets, other forms of power do.

Exactly how much and what type of power is required for organization and efficiency is a major economic debate of modern times, although it is rarely framed in these terms. Political ideologies from communism to libertarianism make explicit or assumed arguments as to the most efficient levels of organization and how much that efficiency is worth when weight against other values, such as individual liberty or environmental sustainability.

Exactly how much and what type of power is required for organization and efficiency is a major economic debate of modern times, although it is rarely framed in these terms. Political ideologies from communism to libertarianism make explicit or assumed arguments as to the most efficient levels of organization and how much that efficiency is worth when weight against other values, such as individual liberty or environmental sustainability.

These arguments manifest themselves in the laws, the enforcement, and structures of power governing the organization of our economy. Conservatives in the USA, generally trusting of the market and distrustful of government, take a bare-bones approach to economic policy. Their professed preference is for a smaller fiscal footprint of the government in the economy and limited government regulatory influence as well. Liberals (in the American sense) are more critical of private forms of power, such as corporations, and view the use of government power to actively shape market outcomes more favorably. These differences are substantive but nevertheless dwarfed by differences between the US system and other economic systems seen in the past century, such as Soviet-style communism or the vast variety of economic systems found in the developing world.

~~

What was it again that these political perspectives and associated market-shaping policies had to do with making bread brown and crispy?

Presumably, the exorbitant price tag on the homemade toaster ensures that it will never be sold (at least not to be used as a normal toaster). Perhaps upon further attempts the artist/producer would improve his toaster production and bring down price somewhat, but we can assume it would never be able to compete on price or quality with the typical goods it would sit next to on the shelf at Wal-Mart or Tesco. In effect, the artist will not be able to make money producing normal toasters on his own because he is unable to produce enough value that people will pay him for. His labor costs too much, and therefore he does not possess the requisite productivity to effectively compete.

Like any producer, requisite productivity for a toaster maker derives from two things. First: the costs relative to how much people value his toaster—it is unlikely he will find many buyers for £3,000 toasters. And, second: the costs for his toaster relative to his competition’s costs—if there was no-one making a cheaper toaster, he would perhaps have been able to sell one or two to rich people. As it stands, however, there are clearly classier toasters available for less price.

The existence of value that people will pay someone for is a function of scarcity, which in turn is a function of both supply and demand. This is another way to think about who can sell toasters: individual producers of toasters are unable to supply goods at market prices because large, highly organized producers integrated with the world market are able to produce much more cheaply, bringing down the costs.

But is it not a good thing if specialized production brings down costs? What is the problem here?

One potential area for problems arises from the interaction between power and cost structures. Like power, cost is often a zero-sum game: "there's no such thing as a free lunch." Organizational power leads to economic power, but this economic power may leave weaker players with the shorter end of the stick. The organizational power of corporations allows us to achieve impressive economies of scale in many markets (including the breakfast food preparation appliance market). But it also tends to concentrate economic power at a level far above the individual.

~~

We cannot make toasters from scratch for a living. If browning bread is our true passion, we can join the specialization chain at some point, designing electrical toasting circuits or stylish new chrome shapes to sit on our countertops. This chain is brilliantly inexpensive and can benefit consumers, but the organizational power required to maintain specialization also concentrates economic power within the production process.

Hopefully I am being somewhat clear. The problem is not that people are getting more productive and therefore costs are going down. That is good. If you are more productive you can just sell more and make more money.

The problem is also not that we have to specialize. Specialized producers could still trade their production for a fair market value.

The problem is when the only way to be more productive is by through organization, and that organization itself exerts power in the market (or over the part of the market it shelters). This power can shape the way costs (and I am talking particularly about labor and social costs here) are distributed, squeezed, or eliminated within the chain of production.

~~

We cannot make toasters from scratch for a living. If browning bread is our true passion, we can join the specialization chain at some point, designing electrical toasting circuits or stylish new chrome shapes to sit on our countertops. This chain is brilliantly inexpensive and can benefit consumers, but the organizational power required to maintain specialization also concentrates economic power within the production process.

Hopefully I am being somewhat clear. The problem is not that people are getting more productive and therefore costs are going down. That is good. If you are more productive you can just sell more and make more money.

The problem is also not that we have to specialize. Specialized producers could still trade their production for a fair market value.

The problem is when the only way to be more productive is by through organization, and that organization itself exerts power in the market (or over the part of the market it shelters). This power can shape the way costs (and I am talking particularly about labor and social costs here) are distributed, squeezed, or eliminated within the chain of production.

No comments:

Post a Comment